Let’s take a look at the foundations of contracts in pictures.

In the last post about a Pareto optimum, we saw that A and B would trade from an initial allocation until they reached a point where their indifference curves were tangent to each other. That point is a Pareto optimum given the initial allocation of goods between A and B. At the Pareto optimum, the two indifference curves have the same slope.

Question: Why do the indifference curves have to have the same slope at the Pareto optimum? Suppose the curves are differentiable. What would it mean for the curves to have different slopes at their point of tangency?

Mathematically, the magnitude of the slope (that is, -1 times the slope, since the slope is always non-positive) is called the marginal rate of substitution, which we’ve met before. So let’s restate the common tangency at the Pareto optimum in economic terms: at the Pareto optimum the marginal rate of substitution of good Y for good X is the same for both A and B.

The intuition here is simple: the marginal rate of substitution (MRS for short) of Y for X measures the amount of good Y that a person is willing to exchange for a unit of good X. When the MRS of Y for X (that is, the slope of the indifference curve) is the same for both A and B, then the amount of good Y that A will give for a unit of X is exactly equal to the amount of Y that B will accept to part with a unit of X. B will not accept any smaller amount of good Y, and A will not offer any larger amount of good Y, so no mutually beneficial trading is possible. That state- the state of not being able to trade to mutual advantage- is a Pareto optimum.

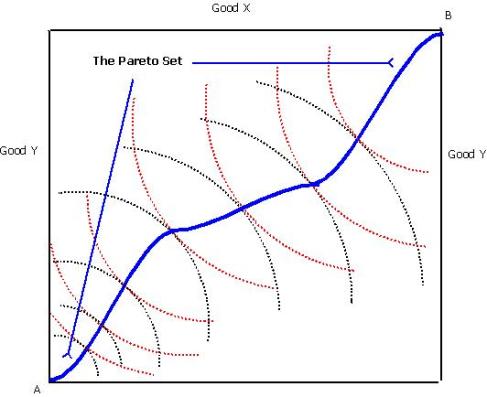

The set of all possible Pareto optima in an Edgeworth Box is called, unsurprisingly, the Pareto Set. It is the set of all points where A and B’s indifference curves are tangent to each other. For example, the blue line in the diagram below is a Pareto Set.

Question: Does the Pareto Set have to pass through the origins of both A and B?

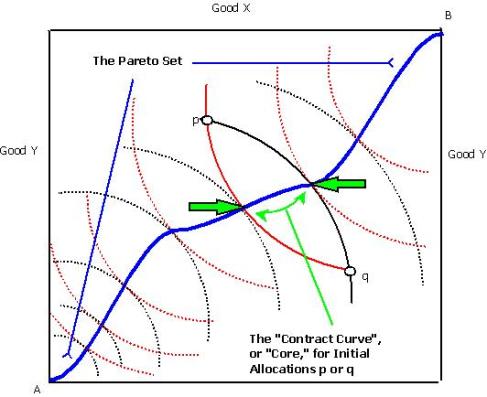

Every point in the Pareto Set is a Pareto optimum for some initial allocation of goods X and Y. However, A and B cannot trade from any initial allocation to any point in the Pareto Set. The set of Pareto optimal points that A and B can trade to from their initial allocation is called the Contract Curve or the Core for A and B, given their preferences over X and Y (that is, their indifference curves) and the initial allocation of goods (that is, some point in the Edgeworth Box).

The Contract Curve (or core) is a subset of the Pareto Set. In the diagram below, the contract curve for initial allocations p and q is the same. It is the segment of the Pareto Set between the two green arrows.

How does this matter to contract law?

Well, to take a first pass, suppose the initial allocation were p. If A & B are rational, then a few possible rules for interpreting contracts are the following

- they must write a contract that brings the allocation inside the lens defined by p and q;

- for any contract inside the lens that is not on the contract curve (or in the core), they could have written a better contract, namely, one that brought the allocation onto the contract curve;

- if the allocation between A and B is challenged in court, and determined to already be on the contract curve, then court should not disturb that allocation;

- if the allocation between A and B is in the lens but not on the contract curve, then the court should disturb the allocation only to bring it on to the contract curve of the new lens defined by the challenged allocation.

Question: Evaluate these rules. Are any of them too restrictive or too broad? Do they make sense? Can you suggest better rules?

Implied Terms and Vitiating Doctrines:

Assume that a court knows the original allocation p between A and B. Then, if it finds that the contract re-allocated the goods to a region outside the lens defined by p, then that is a reason to vitiate the contract. The contract is irrational. In order to vitiate the contract, the court can use a variety of doctrines, such as impossibility, foreseeability, mutual mistake, and unconscionability.

But vitiating a contract is a heavy-handed and rare approach. The court can often attain the same result by implying terms into the contract that change the allocation that the contract appeared to make.

Bargaining Power:

Now rational behavior implies that A and B will bargain from p to some point in the core. But which point will it be? Not all points in the core are equally preferable to A and B. A will prefer a point on the contract curve that is further right, while B will prefer a point further left. Points in the core are, however, mutually preferable to any points not in the core (that is, A and B can trade to mutual advantage to get on the curve, but not to get off it). If A and B have the same bargaining power and are perfectly rational, then their initial allocation will determine a particular point on the contract curve. However, if their bargaining power is unequal, then they may reach the curve at a different point- further left if B is a better bargainer; further right if A is.

Incomplete Information and Imperfect Information:

Incomplete information and Imperfect information are terms that you will commonly see in game theory. We introduce them here to better understand the court’s position when a contract dispute is brought to it. Any contract case can be simplified to a “game” with the following elements.

- Players (the contracting parties and/or the court);

- Strategies (e.g., the various contracts the parties can write, the challenges that they can bring in court, and the various interpretations the court can give to the contract); and

- Payoffs (the preferences of the parties and of the court)

Now if the court is to interpret the contract to make both A and B better off, then it must know the payoffs or preferences of both A and B. In real life, there is no guarantee that it will.

A game in which a player does not know the players involved, strategies available, or payoffs in play is called a game of incomplete information.

Thus, if the court does not know what A and B’s indifference curves look like, then the court has incomplete information. Similarly, if the court does not know whether the contract was between A and B or between A and C (with B acting as C’s agent), then the court has incomplete information. Generally, the court will know the strategies available to A and B, since these are just the contracts that they could plausibly write. Still, it is possible for the court to think that A could write a contract that, in fact, she could not, for lack of authority or bargaining power. Think, for example, of a private person’s negligible ability to bargain for terms with an insurance company or any large corporation. It would be hard for a student to bargain with a college to change evaluation criteria, even if they did make both sides better off.

In contrast, a game in which a player knows all the players, available strategies, and payoffs, but not the specific action that each player took, is called a game of imperfect information.

A game may have complete but imperfect information: everyone (all players) may know what everyone could do (all strategies), and how everyone would feel about any given state (all payoffs), but not know what anyone actually did do (action played).

Incomplete information games where the players’ preferences are unknown can be converted into imperfect information games via the Harsanyi transformation, which we may discuss later.

However, the usual criticism of courts intervening in contracts is precisely that they have incomplete information about the contract that they are intervening in.

Another criticism of courts is that their own preferences are unclear when they engage in contract interpretation. We know that A and B are trading for the same goods and will trade to mutual advantage. However, when the court re-allocates between A and B, it is not taking either good for itself, and is not engaging in any obvious bargaining. It is harder to see why the court’s intervention will make everyone better off.

The Coase Theorem again:

If the court does intervene and gets the contract wrong, then the consequences of court error depend on three things (i) adjudication costs, (ii) transaction costs, and (iii) the new allocation.

By deciding the case, the court will have simply set a new allocation, and the Coase theorem tells us that the initial allocation will not determine the final allocation if the gains from trade exceed transaction costs. Parties will bargain to an efficient allocation (i.e., to somewhere on the contract curve defined by the new allocation).

However, adjudication costs matter because it is not costless for the court to decide a case. Parties spend on litigation and the court spends government resources on hearing and deciding the case. If parties would have bargained to an efficient allocation without (and also in spite of) court intervention, then the costs of adjudication are a dead-weight loss.

Transaction costs matter because the Coase Theorem only implies an efficient allocation when the transaction costs are low. If they are not lower than the gains from trade, then the court’s initial allocation will be the final allocation.

Does (iii) come as a surprise?

We have already discussed in class that the court’s reallocation will have redistributive effects. Even though the parties will reach an efficient allocation when transaction costs are negligible, the particular allocation that they reach will be different. Not all “efficient allocations” are created equal. Which efficient allocation is reachable depends on what the initial allocation was.

In class, we discussed how one party will be richer or poorer depending on the initial allocation, even where the final allocation is the same. The Edgeworth Box is a generalization of that discussion.

Specifically, in our Edgeworth box, let good X be a right, (say the right to cause or stop pollution) and let good Y be money. Then it is true that the parties will bargain to some point in the Pareto Set (by the Coase Theorem). However, which point that will be depends on the initial allocation. The initial allocation will define the contract curve, that is, it will choose the segment of the Pareto Set that the parties are able to bargain to. The court’s allocation, then, will determine which core (subset of the Pareto Set) the parties can reach.

Question: Can you use the Edgeworth Box to show examples of how Coasean bargaining can redistribute wealth between A and B depending on the the court’s allocation? If any allocation that is reached is in the Pareto Set, then does it matter which one is reached? Is there any criterion to prefer one point in the Pareto Set to another?